MadAminA! Feature

Concert Band — An American Legacy

On a day in late May, 1980, an article appeared on the first page of the Metropolitan Section of The New York Times announcing the unavoidable cancellation of the Guggenheim Concert Band’s summer season and the Band’s impending dissolution. It was more than a routine cultural obituary. It was thought by some to be a formal acknowledgement that an era had ended and was shortly to be consigned to oblivion. Sadness and sympathy, especially among senior citizens. Millions of New Yorkers’ summers have been enriched for years by the Goldman Band, the ensemble’s name from 1928 to 1979 when it was renamed in honor of the family which had sponsored it throughout its existence. Goldman or Guggenheim, New Yorkers were about to face a bandless season and, although the more elitist elements in musical circles remained woefully silent, more populist connoisseurs found it difficult to stay stoical.

And then, a few days into June, an unexpected sequence of events occurred to reverse destiny, bring about a bustling season, and hopefully to assure a long and happy future for New York’s only professional concert band and its enthusiastic, loyal following. This is the story of a sociological phenomenon in music.

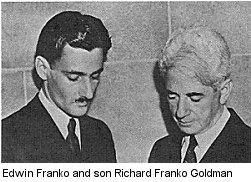

Edwin Franko Goldman, born on January 1, 1878, in Louisville, Kentucky, was a good deal more than an instrumentalist. True, he was an accomplished cornetist who had the solo chair in the Metropolitan Opera orchestra, already one of the nation’s finest at the turn of the century. But his musical discipline and disposition were far broader, his energies far deeper, and his commitments far more comprehensive than to restrict himself to an orchestral musician’s career. He had studied composition with Antonin Dvorak and, in 1911, founded an ensemble which, by 1918, became a treasured part of New York life and the finest concert band in the country, offering a regular summer season of free concerts. The Goldman Band was noted not only for its skill and musicianship but for its unusual repertory, including many modern works especially written for the Band. As a composer, Goldman produced more than 100 brilliant marches as well as other band music and music for various winds, and studies and methods for cornet and other brass instruments. He was the founder and first president of the American Bandmasters’ Association and was said to wear the mantle of the great John Philip Sousa (1854-1932). It is self-evident that Edwin took a central role in the musical education of his son, Richard Franko Goldman, who, in addition to succeeding his father with the Band, was director of the Peabody Conservatory, composer of many works, author of several books, and founder/editor of the Juilliard Review. During his 24 years at the helm, Richard Goldman carried the torch of the very highest standards of musicality and versatility and lent his considerable reputation to the standardization of band instrumentation. In 1964, Ainslee Cox became co-conductor of the Goldman Band and, upon the death of Richard Franko Goldman in January, 1980, was appointed music director and conductor of the band under its new name, the Guggenheim Concert Band.

As the new decade dawned, money became a horrendous problem. The City of New York had never given any financial support to the Band. By the spring, the Daniel and Florence Guggenheim Foundation felt that it could no longer be the sole source of support and suggested that additional sponsorship be sought. It was a poor time for fund-raising. The City had, in fact, reduced its spending and was actively soliciting funds for existing cultural programs from the corporate sector. When little came in, it was felt that the time had perhaps come to stop. A press release was prepared. The plug was about to be pulled.

A reporter and foundation expert for The New York Times, Kathleen Teltsch, got hold of the story, became keenly interested, researched the problem thoroughly, wrote an initial article and periodic follow-up pieces as funds and pledges began to come in. She became so involved as a catalyst that she took herself off the story. (“I’ve never seen anything like it, and I’ve been involved with a lot of organizations that have been in trouble,” said Ainslee Cox.) Her efforts produced the infusions needed to make the 1980 concerts possible. The Daniel and Florence Guggenheim Foundation agreed to match new funds and was quickly joined by the Louis and Anne Abrons Foundation, The Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, Lehman Brothers Kuhn Loeb Inc., the Music Performance Trust Fund, and the XOIL Energy Marketing Group Inc. led by Eric W. Goldman (no relation). At the half-past-eleventh hour, they were off and playing!

Cox and his colleagues are intensely aware of the extraordinary tradition which the Band represents. Just as the Boston Pops has always stood for a perfect melange of musical and social elements, so has the Band; both have achieved a high performance calibre, regardless of the type of music being played. Thus, the Band has from its very inception appealed to a broad audience which comes not because it’s the fashionable or politically prudent thing to do, but because it wants to. Goldman père et fils as well as Cox have never pampered or pandered. They have performed the widest possible spectrum of music and have made their listeners feel that if some thing is played which doesn’t please them personally, something else will come along shortly which will.

Thus, in addition to the plethora of transcription of the classics and the spunky marches or Broadway medleys, there have been compositions by the most contemporary of composers, from Henry Hadley to George Perle (Solemn Procession) and Matthias Bamert (Inkblot). Not only American composers were eligible for performance. Albert Roussel wrote a piece for the Band. So did Respighi, Milhaud, and Shostakovich. When Arnold Schoenberg came to this country, he wrote his Theme and Variations for the Band. (Richard Goldman was in the army and the premiere had to be postponed until after the orchestral transcription had been performed. It finally took place in Town Hall at a concert sponsored by the League of Composers.) But of course American composers were the prime beneficiaries of the Goldmans’ vision, rising to the occasion by writing some of their finest music, such as Virgil Thomson’s A Solemn Music, specifically in the band medium. The tradition continues to the present. This season’s premieres included Gems From Spoon River by Francis Thorne and a piece by Michael Valenti originally written for Blackstone. The magician heard about the performance and showed up, stunning performers and audience alike by performing magic tricks in Damrosch Park! What fun!

And yet, problems abound. There is still a “schizzy” ambivalence surrounding the concert band. Noses still wrinkle at the thought of it, and condescending jokes are made about oompahs, football, drum majorettes with naked knees, and poor music played poorly. In an age which has produced the $50 opera ticket and the 52-week season for symphonic musicians, what can one say about a medium which numbers hardly any professional (paid) bands giving ongoing concert seasons — the Detroit Concert Band is another exception — and whose audiences get in free? The vast majority of bands are either military (paid for by tax dollars) or university. Although the latter category is, by definition, non-professional, it often produces a virtuosity which can boggle ear and mind. Listen some time to one of our better college bands — and there are many — playing a Guy Duker transcription of a Hindemith work or one of the Husa originals, Music for Prague 1968 or Apotheosis of This Earth, and ask yourself how many symphony orchestras, here or in Europe, attain such a level of proficiency. Ainslee Cox: “The high school and college band and the church organist are the most unrecognized musical force in this country. They set the musical tone nationally.” Increased communications between amateur and professional bands such as the Guggenheim might be regarded as enlightened self-interest. “Major college bands across the country follow our programs very much. If we perform a piece, it gets known very quickly that we’ve done it and, in that way, we’ve been able to help composers and publishers somewhat.”

Can the professional band coexist with its military and university counterparts? The generosity and support of individuals, corporations, and government are the only ultimate hope. Senators Javits and Moynihan have given much encouragement. Peculiar as it may sound, the National Endowment for the Arts, without which virtually no cultural organization could long endure, still has no program to assist concert bands. The New York State Arts Council, which thinks nothing of funding events that are studiously avoided by all but the most parochial audiences, has declined aid on the grounds that they only fund deficits. (Cox: “We don’t do concerts unless the money’s in the bank.”)

And so, the path is strewn with obstacles large and small. None, however, has been able to pale the luster of the 1980 season or to dim the affectionate enthusiasm of the audiences which have crowded Seaside and Damrosch Parks on Wednesday through Sunday evenings for seven weeks in New York’s good old summertime.

MadAminaA! Quick Index

principal news stories | feature stories | encounters

words n’ verse | editorials & commentary

© by Music Associates of America. All Rights Reserved

music associates of america // 224 king street // englewood // new jersey // 07631