Harmoniemusik (Wind Music) from Mozart's Abduction from the Seraglio

by Wolfgang Plath

Mozart's letter of 20 July 1782 from Vienna to his father in Salzburg plunges us right into

the problem. In it we read: "...Now I'm really up against it — my opera must he transcribed for winds by a week from Sunday or else someone will get there ahead of me and reap all my profits; and I'm supposed to be doing a new symphony as well — how is all that possible! you won't believe how hard it is to transcribe something like this for winds so that it's really perfect for wind instruments and at the same time that the original flavor doesn't get lost — Oh well, I'll have to work nights, otherwise it can't be done — and it is to be dedicated to you, my dearest father — you should be getting something in each mail — and I'll write just as quickly as possible and write as well as haste will allow. —"

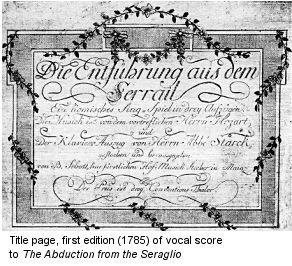

"My opera" : that is The Abduction, K. 384, had premiered only a few days previously; the "new symphony" that Leopold Mozart intended with such apparent urgency for Salzburg is the Haffner Symphony, K. 385. And the wind transcription of the opera, what's with that? Did Mozart really write it, or did he only plan to write it? Is it, insofar as it might ever have existed, still extant today, or must it be regarded as having disappeared forever, i.e., lost? That precisely is the cardinal question. We will return to it.

First we should consider the next question: what actually does Harmonie or Harmoniemusik mean?

No definition is found in ancient dictionaries, but clues are given in more recent editions and newer publications. Thus, we learn that Harmoniemusik is "in contrast to strict brass music, a wind orchestra consisting of mixed woodwinds and brass instruments..., as is typical, above all, for military music" (definition in the Riemann-Musik-Lexikon of 1967). Such wind music is normally scored- or at least it was in Vienna during the 1780's-for 2 x 4: two each of oboes, clarinets, horns and bassoons, making up an octet.

No less a personage than Emperor Joseph II himself institutionalized the royal winds (k.k. Harmonie) as a set ensemble in the spring of 1782. In doing so, he could count on the outstanding winds of the royal National Court Theatre Orchestra in which such excellent virtuosi

as Johann Georg Triebensee and Johann Nepomuk Went (oboes), the Stadler brothers (clarinets), and the hornist Jakob Eisen were on staff. This Royal Harmonie played at banquets but did not serve as a military band. Its calling card was its repertory: above all, they played wind arrangements from operas and ballets — and the principal arranger of these pieces was the above-named Johann Nepomuk Went (Wendt, Vent, or however it was spelled).

Touring virtuosi spread the news of this legendary wind ensemble throughout the land. Writing in his Hamburger Magazin der Musik (20 December 1783), Carl Friedrich Cramer reviews a concert of the Boeck brothers, hornists of Count Batthyanyi's Court Ensemble of Pressburg:

"...Among the news of the music world that the Brothers Boeck told me was something of particular interest to me: namely, of a company of virtuosi organized by Emperor Joseph II, exclusively made up of wind instruments played by the most outstanding players in the world, which has become known in Vienna as the Royal Harmonie. This society of 8 people presents a full-fledged concert in which they perform things that were actually intended only for voice, arranged by one of them, the virtuoso and composer Wehend [Went] for the Harmonie, such

as: choruses, duets, trios, even arias from the best operas; in which the oboe and clarinet take the place of the voice. They also told me the names of the individual musicians...."

The Royal Harmonie in Vienna served as a model. All over Austria and southern Germany, such wind ensembles cropped up, or existing court bands established such core groups. Concurrently, the demand for such opera arrangements skyrocketed. Making arrangements for Harmoniemusik accordingly became a new way for musicians to supplement their incomes: they only had to be quick enough in their craft.

All this by way of background to the above-cited Mozart letter of 20 July 1782. At the very least, it is clear that Mozart was eager to make the wind arrangement of his opera himself, as time-consuming and tedious as the business may have been, envisioning rich rewards provided that he was the first to hit the market.

Up to this point, everything is clear. The difficulty only arises in that there isn't such a thing as a Mozart wind transcription. Did it never exist? Did it get lost? Was it merely misplaced so that it could show up again today or tomorrow? Official Mozart scholarship has for long been cautious in addressing this question. Surely it was correct in its caution: a contemporary Harmoniemusik of The Abduction from the Seraglio that was presented with much ado in the 1950's as apparently authentic was revealed some years later as an arrangement by Johann Nepomuk Went. Prevailing opinion, therefore, was that, despite Mozart's intention, so clearly expressed in his letter, to arrange his opera himself, he was never able — for whatever reasons — to realize the plan, perhaps because time simply got too short and one of his competitors got there ahead of him.

Recently the situation changed once again. In the spring of 1983, the Dutch conductor and musicologist Bastiaan Blomhert stumbled upon a set of wind parts in the Royal Library (Fürstl. Fürstenbergische Hofbibliothek) of Donaueschingen (Mus.Ms.1392), that, although not entirely unknown to prior research, had never — for whatever reasons — been thoroughly examined before. On the title page of each of the eight pages: Die Entfuhrung / Aus dem Sereil / Eine komische Opperette in 2. / Aufzügen / v: H: Mozart" and contain no less than sixteen arranged pieces from the opera. Blomhert, at that time still conductor of a wind ensemble, was sufficiently curious to prepare a score from the set of parts. On closer study of the pieces, he was struck by the extraordinarily high quality of the wind settings; in addition to a notable freedom of the arrangement vis-à-vis the original version. Finally, the uncommonly extensive dimensions of the entire work (duration over 60 minutes!) was mysterious, and seemed an unmistakable signal that this Harmoniemusik differed sharply from all other known arrangements of this sort.

Blomhert compiled all these seeming peculiarities and came to the conclusion that the Donaueschingen Harmoniemusik from Abduction could hardly be anything other than a copy of Mozart's own arrangement that had been believed lost.

— Translated by George Sturm |