Sharing the Musical Wealth

Music Librarians Celebrate and Plan by D.W. Krummel

Last year the Music Library Association marked its

fiftieth birthday. Well over 400 celebrants from most every state, Canada,

and several overseas countries, made the pilgrimage — to New Haven, in February,

no less — addressing themselves to the past and to the future — the whys,

wherefores, and whithers — of the tens of millions of musical documents in

the custody of hundreds of collections, as needed and used by tens of thousands

of readers every year.

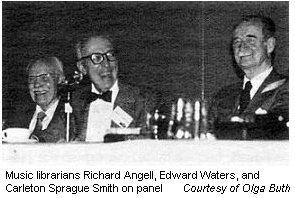

From its beginnings in 1931, also in New Haven, the M.L.A. has been made up of two kinds of people who work in music libraries: the librarians and the readers. In 1931 the librarians came

mostly from places like the Library of Congress, the New York Public, and a handful of major universities; today they also come from Appalachian State and Trenton State, Washington State, West Chester State, and several Cal-States; from the Austin Public, the Trenton Public, the Atlanta Public, and the Carnegie in Pittsburgh; from St. Olaf, Stetson, and Middlebury; from the Arnold Schoenberg Institute and the Country Music Foundation; not to mention Curtis, Peabody,

and New England Conservatories.

Readers come to such repositories looking for the scores, books, and recordings —

often only for the information — they need. Often they don't know exactly what they do need, providing some of the most interesting assignments of all to librarians; often the information

or the source is quite different from what was expected, or new or obscure so as to be inaccessible in the library's resources. Here, in any event, comes the casual but intense amateur, or the local radio station, for biographies of rising performers and minor composers who need to be better known; the choir director in search of Renaissance choral music, SATB and sounding like Brahms; the retiree for the hymn she or he sang 70 years ago; the local orchestra manager needing an unusual address; or most any musician, to scan the back-file of a specialized music periodical. My own bete-noire

for 17 years, for an American literature friend: an internal line of a musical comedy song of the 1920s, "There's no disputin' that old Rasputin ...."

Understandably, many readers — musicologists, also administrators, composers, performers — recognize that they have used music libraries, for these and countless other matters, often and significantly enough to justify M.L.A. dues, and sometimes active participation as well. Over

its fifty years, the M.L.A. has numbered among its presidents and board members such musicologists as Charles Warren Fox, H. Wiley Hitchcock, Manfred Bukofzer, Nathan Broder, and Howard Smither. Its present membership includes composer Aaron Copland, music administrator Leonard Feist, pianist Rudolf Serkin, and music editor Kurt Stone (not to mention 1800 others).

Its activities are built around an annual late-winter meeting, and focused through a happy confusion of committees, through which a variety of special concerns are addressed. While some music librarians work with the public on matters like those mentioned above, others are at work behind

the scenes, figuring out how to cite the works of Mozart so that readers can find what they want; sorting old programs of local musical events, to provide an archive for future historians; discovering and filling gaps in the collection; and laboring over the inevitable memos and reports, budgets, staffing duties, space and equipment problems, and administrative planning necessary in even the smallest of collections today.

An array of special M.L.A. publications supports this work: a Newsletter reporting

on Association activities; an "Index Series" of reference tools for librarians and specialist researchers; a set of "Technical Reports," a monthly Music Cataloguing Bulletin, and occasional single publications. Most important of all is the quarterly journal

Notes, which contains the most extensive general section of reviews of new books and music of any journal in existence; articles on general music and music-library topics; a venerable "Index to Record Reviews;" an annual necrology index, miscellaneous other regular features, and advertisements that are consulted often enough to demand their own index. Through such

publications, music librarians have maintained their enviably close and respectful relationship with those who use music libraries.

Sharing, of course, is what provides a sense of community. In a sense, library work itself is a service in sharing; the library serves basically as an "interface" between a potential audience of readers and the vast wealth of books, scores, recordings, and ephemeral materials

that make up our collections. Among music librarians themselves there is also a happy spirit of sharing - of materials via loan or photocopy when appropriate and when conditions permit; of expertise in answering tough reference queries; of bibliographical records, so as to save the time and cost of each library performing the same identical cataloguing operation; of advice and

experience in dealing with comparable administrative situations. "They're sharers" — such was the remark overheard at the New Haven meeting. Not of confidences, one hopes; rarely of their favorite donors, one suspects, understandably and understandingly; but of the wide range of facts and expertise that becomes part of the daily performance of regular tasks and special assignments.

Music libraries and M.L.A. alike are flourishing today, although there can't help but be some dark clouds on the horizon. The costs of materials are increasing many times faster than library budgets. Automation is providing a new timeliness, but (it is generally agreed) no cost savings at all, and considerable and continuing internal upheaval as well. Librarians like to see themselves as more catholic than their predecessors in tastes and competence. Maybe true, maybe not, but what is obvious is that the information sources and systems they need are immensely more complicated. As collections themselves expand, they usually get even more expensive to maintain, and harder to use.

While the narrow world of institutional music libraries per se is hardly a "growth industry," there are some happy signs that the larger world of music libraries is becoming

even larger. For years librarians, in moments of euphoria, have dreamed of the "library without walls;" and thanks to recent demographic trends in the small community of music librarianship, together with a good deal of residual good will and respect, this may be coming about more than we

have realized. It has long been common for music librarians to move out into either general library or academic music positions. Less conspicuous has been the mobility into the communities of music trades and administration. In the course of their work, and sometimes as a result of their training,

music librarians naturally develop some special knowledge of music copyright, music information sources, and of the special needs of various kinds of musicians. By a process of self-selection,

librarians are usually endowed with the instincts for correct detail and for the provision of service. It is then perhaps only natural that respected members of the music library community have lately taken up positions in music publishing and orchestral management, in copyright law and in work with performance rights. The rich world of music librarians thus stands to become even richer as an even more pervasive part of the wide world of music.

This very richness becomes a problem in its own right. The first fifty years of M.L.A. were times of establishment and recognition; the next fifty may well be appropriately devoted to problems of "musical information overload." Thinning our collections in a time of increasingly sophisticated audiences (like shooting the proverbial piano player) won't help. Closer attention

to the specific needs of the musical community, on the other hand, should become all the more important. Our crystal balls may be cloudy, but in 1931 they were no doubt just as unclear; our faith has to lie in the same energy and respect that built so much out of so little.

|